“Revofev/The road from Chicago to #decolonizezhigaagoong*”

By: Isiah ThoughtPoet Veney, Ana Croegaert, and Jacob Campbell

*“Revofev” is a new word combining elements of these three words: “revolution of evolution,” and is a song title, from Kid Cudi’s Man on the Moon II album (2010). Kid Cudi (b. 1984, Cleveland) writes openly about struggles with depression and anxiety and this song has special meaning for Isiah: “Music kept spaces of struggle filled with joy and is part of the healing in the face of violence and trauma”.

#decolonizezhigaagoong was a hashtag created for the July 17, 2020 action to remove a statue of Christopher Columbus from the city’s downtown Grant Park, across the street from the Field Museum. Zhigaagoong is an adaptation of the Potawatomi word for Chicago: Zhegagoynak.

Introduction

Isiah ThoughtPoet Veney is a Chicago-based artist, community organizer, and mental health activist whose work centers on the struggle, beauty, and creativity within his community. Grounded in Englewood-by-way-of Chatham—the two Southside neighborhoods with which he most strongly identifies —Isiah’s photographs and prose record scenes of the city’s south and west side majority-Black and brown communities. Ethnographers may recognize Isiah’s images and words as working in the spirit of visual anthropology forged by scholars like Zora Neale Hurston and Américo Paredes.

During the summer quarantine of 2020, Isiah was among the organizers of city residents’ protests for racial justice and felt compelled to use his artistic skills to build a record of his community’s experiences with the pandemic and coincident, ongoing, crisis of racial inequity. He described his sense of responsibility to his community in an interview later that summer with environmental anthropologist Jacob Campbell:

“I felt like I used quarantine, kinda to my advantage as far as like, you know, just, you know, taking photos of like […] what life was being in quarantine, you know, from, I guess, a ‘hood perspective, or urban perspective? And, you know, to be honest, that was really the same thing, you know, like most urban communities already go through, you know, shortages of food, or toilet paper or whatever like that. So, yeah, I think, for me, it was a very reflective moment. And I think it’s a moment that we definitely were not prepared for. But at the same time, we just, like, as far as Black and brown communities, we just kind of do what we do best, which is just adapt.” (Isiah ThoughtPoet Veney)

In communities like Isiah’s, shortages in daily necessities such as food and toilet paper were not new occurrences, and neither was the strategy of adaptation.

This photo essay is a collaboration among Isiah, Jacob Campbell, and Ana Croegaert, and reflects on the challenges faced by residents in long-disinvested neighborhoods in the deeply segregated city. Isiah leads us in the essay, reminding us that, although devastated by racialized urban planning systems and job loss, decades of criminalization, police-sanctioned torture, and lack of adequate mental health care, people in his communities create beauty, express love, endeavor to take care of one another (Contreras 2021). They reach out across neighborhoods and racial difference to build connections that, although fragile, are needed now, as ever.

The essay draws on Isiah’s summer 2020 catalog that was accessioned for the Field Museum’s newly established initiative: The Pandemic Collection. Using a co-curatorial methodology, the collection joins ethnographers, social scientists, and community-based artists and makers to build an archive of the pandemic and simultaneous movements for social justice. Together we selected from among Isiah’s >60 images of protests, mutual aid provisions, vigils, and celebrations. Isiah’s expressive prose (in italics) serve as captions for his images while environmental anthropologist Jacob, along with Ana, a lead curator and ethnographer with the project, offer annotations of the works’ historical and social significance.

The radiance that comes from us learning our past is something to truly behold because our past is so hidden and sacred. It’s our mission in life to tell the stories of pain and loss and how it brought us so much light. There’s rebirth within learning about what once was. We’re still learning that. I’m still learning that..

Muralist Andre Trenier restoring a mural in homage to Fred Hampton and Chicago’s Black Panther chapter. Initially painted by Dasic Hernandez in 2010, the 2020 restoration was supervised by Fred Hampton, Jr.. The mural is at California and Madison, on a building that faces away from the Loop and towards the city’s majority-Black west side neighborhoods that have suffered decades of disinvestment and overpolicing, enabled in part by urban planning designs that intensify separation based on race and class by creating barriers to mobility and connection with adjacent neighborhoods (Hirsch 1983). While some people might initially see the phrase, “the cubs are coming” and associate it with the city’s north side National League baseball team, here it refers to new generations of Black Panther cubs, such as the girls pictured below.

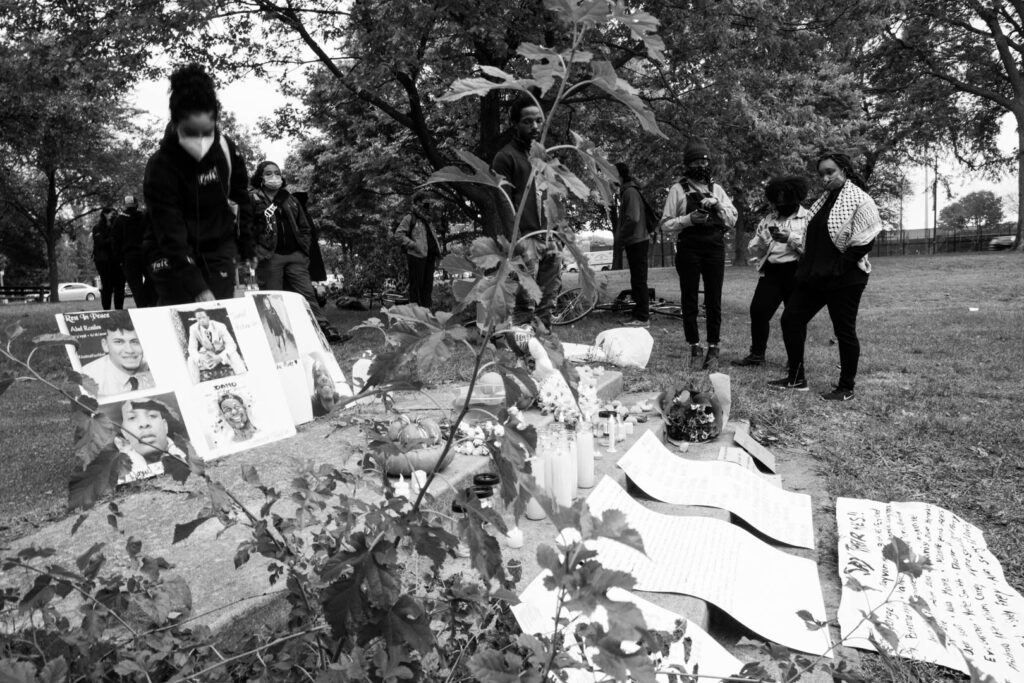

As much as I’m screaming to defend my life I’m still being killed by energies that are supposed to protect my families. As much as I’m begging and fighting to be heard I’m being strangled by others with power and forces I can’t control. I know I must fight on. I know my future depends on my actions now. But in this moment I’m just tired of dying. I’m tired of being strangled..

The families of Black and Latinx survivors of torture by Chicago Police have organized for decades, alongside Black youth-led interracial social movements, to address systems of abuse within the police force and compensate those who have suffered. The city finally took a step towards change by publishing an ordinance and resolution on May 6, 2015, and has had to compensate some of the individuals and their families. During the global actions against police and state violence in summer 2020, Chicago activists continued to demand justice in the face of ongoing abuse, including 40+ years of selectively targeting urban street gangs with the 1970 Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act, the more recent use of big tech through the controversial “Shotspotter” gunfire detection system, and ongoing displacements produced by the demolition of affordable housing and the 2013 shuttering of 50 public schools under the Emanuel administration.

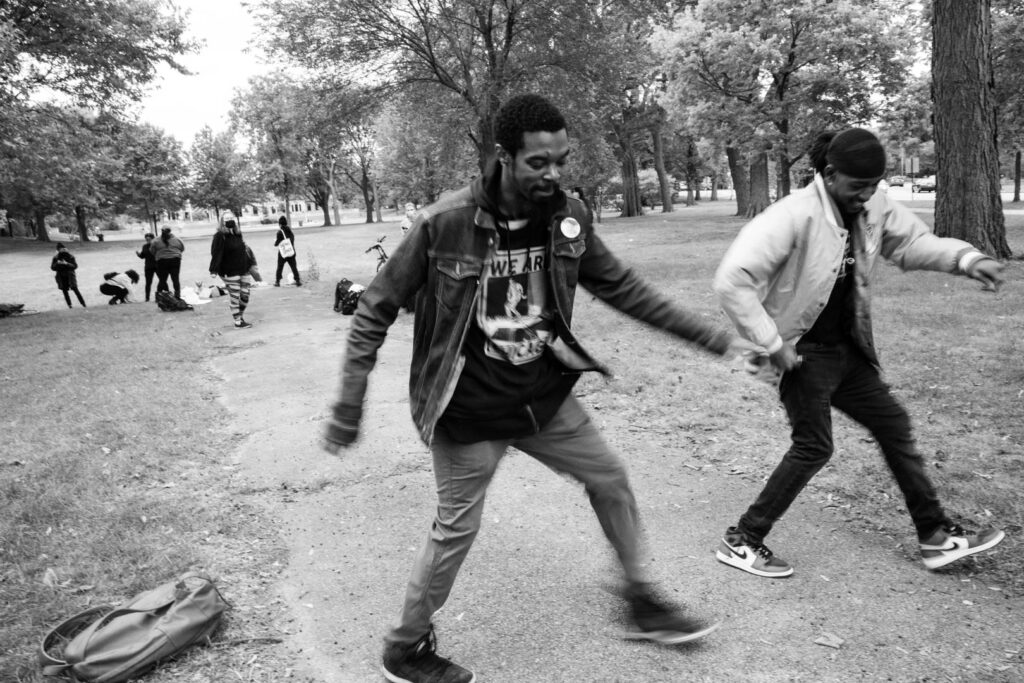

However, we fight back with love and a foundation of pure blk radiance that can’t be reconstructed no matter how the world destroys us. We are wired with a magic that truly has no origin but the dawns of time. That is our best weapon. And for a moment within all the chaos. You can see that we are winning..

The city is alive with young organizers: The Let Us Breathe Collective, Healthy Hood Chicago, Good Kids Mad City, and community-based organizations working for food justice, mutual aid, creativity, the arts, and more. Black women, including queer Black women, are at the forefront of many of these movements. See for example Amanda Williams’ and Tonika Lewis Johnson’s social practice artworks addressing housing in the city.

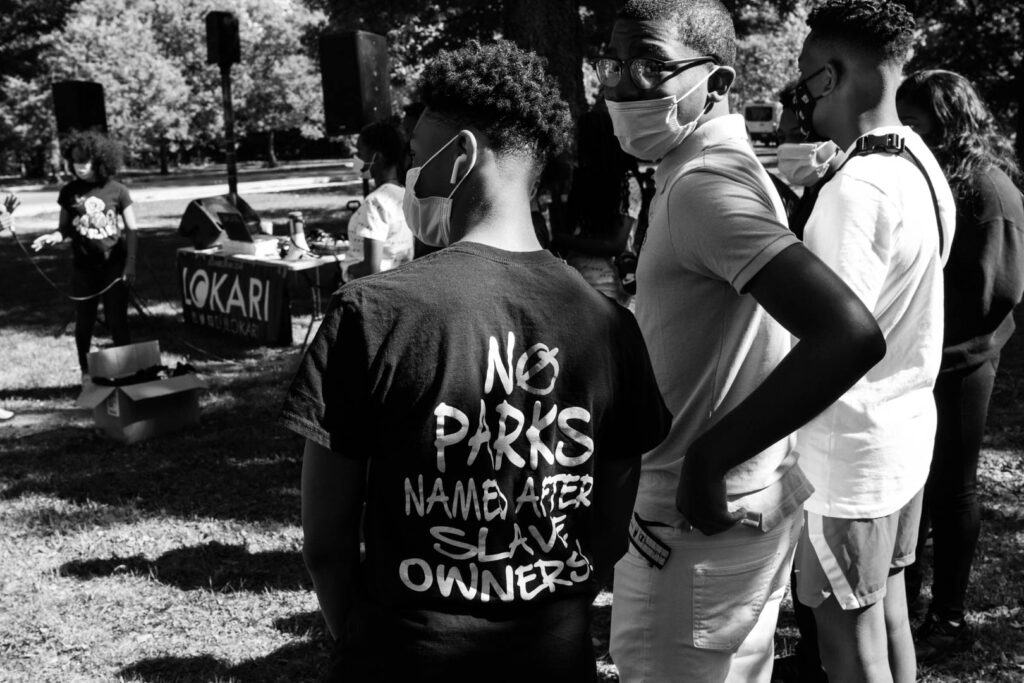

Chicago parks have always been sites where immigrants and oppressed people have struggled for rights, forged identities, and found joy in social connections – often at the same time. As Colin Fisher (2015) demonstrates, in the late nineteenth century, trade unionists, socialists and anarchists – many of them recent immigrants – regularly congregated with their families for leisure in Chicago parks on days off work. Simultaneously, they organized collective actions, such as the strikes for an 8 hour work day in 1886, which inspired May Day as an international workers’ holiday. Through the first part of the twentieth century Bughouse Square (the popular name of Chicago’s Washington Square Park) was one of the most important outdoor free speech centers in the nation where activists, primarily from the revolutionary left, soapboxed regularly. There is an unbroken line between those early park gatherings and the activations captured in these 2020 images.

In 2020, after years of organized protest primarily led by Black youth, a park in Chicago’s North Lawndale Neighborhood formerly named after U.S. Senator and slave owner Stephen A. Douglas officially became recognized by the Chicago Park District as Douglass (Frederick and Anna) Park, after abolitionist Frederick Douglass and his wife Anna Murray Douglass. The city park and the street are democratic spaces, where the right to free speech and assembly is legally protected (albeit threatened in reality) and the status quo can be challenged. In Chicago these spaces serve as platforms where injustices are named and changes demanded.

Our prism of normalcy was broken eons ago when we decided to rebel against the world that kills our souls just because we created this world and they didn’t. Our new form of freedom fighter is outcast and heartbroken. Our new form is the form we’ve always known..

Our ability to win in every war we don’t deserve to be in shows how persistent our love for our future is. We battle and still build community. We fall and still create the path for our children and the world they need next. We aren’t vanishing like you want. We aren’t the death of your ignorance. We are angels destined to change society in the form of delinquents. We are the answer to unchanged histories you know of. We simply are..

Works Cited

Contreras, Ayana. 2021. Energy Never Dies: Afro-Optimism and Creativity in Chicago. University of Illinois Press: Champaign.

Fisher, Colin. 2015. Urban Green: Nature, Recreation, and the Working Class in Industrial Chicago. University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill.

Hirsch, Arnold. 1983. Making the Second Ghetto: Race and Housing in Chicago 1940-1960. University of Chicago Press: Chicago.

You may republish this article, either online and/or in print, under the Creative Commons CC BY-ND 4.0 license. We ask that you follow these simple guidelines to comply with the requirements of the license.

In short, you may not make edits beyond minor stylistic changes, and you must credit the author and note that the article was originally published on Home/Field.