It was a particularly muggy late spring afternoon in 2022 in Tompkins Square Park in Manhattan. A rally, followed by a march starting in the park was called for that day in protest of the violent sweeps of homeless encampments initiated by Mayor Eric Adams earlier that year. The location of the park was symbolic. The 1988 Tompkins Square Park Riot was a homeless sweep that turned into clashes with the police. More than thirty years later, these commons had once again become the target of anti-homeless policies. For weeks, the police had been clearing out the homeless and activists attempting to protect the encampments. Sanitation vehicles aided in these raids, trashing the tents, blankets and whatever else homeless individuals could not salvage. Between March 18th and August 31st of that year, the city cleared 2,331 camps. Yet, despite city workers reaching out to 1,442 people at the encampments, only 97 people accepted shelter.

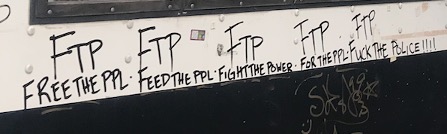

That day, our mutual aid group’s collectively owned truck, decorated in graffiti by local artists, pulled into an illegal spot across from the gathering of activists and homeless who had made the park their residence. Activists on the scene helped grab the tables, coolers of water, and other items we intended to distribute that day as we unloaded the truck and hoisted them over a chest-high fence dividing the park from the sidewalk. Throughout the afternoon, we handed out sleeping bags, tents, backpacks, hygiene kits, and black adjustable caps, among other items regularly confiscated or destroyed during these sweeps. Water and snacks were on display for anyone to take. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), mainly masks and sanitizer but also Advil, was available. Aerosol bottles of sunscreen were readily used as the sun was particularly harsh, cutting through the hazy sky. All these items, which had been purchased through donated funds or collected through in-kind donations, were free for whoever needed them: protesters and passersby alike. No questions asked. By the time the march stepped off from the park, most of the supplies we brought had been distributed and we returned to Queens to drop off empty bins and park the truck.

In this vignette, I am centering the gaze of our group, whose labor and ethics of distribution encapsulated the definition of mutual aid as the “collective coordination to meet each other’s needs, usually from the awareness that the systems we have in place are not going to meet them” (Spade 2020, 7). I especially engage with mutual aid groups coming out of the Covid-19 crisis and the values that shape their work. These values lie in the acts of solidarity of supporting protests through the distribution of supplies. They also manifest through non-hierarchical acts of distribution, that is, the refusal of means testing, policing needs or paperwork. Finally, there is a politicization of abundance, mobilized by mutual aid organizations as a response to municipal policies of austerity in the wake of the pandemic.

Here, I focus on two interrelated parts of Eric Adams’s political agenda, for which he and his administration invoked a language of crisis: increased homelessness and the resettlement of asylum seekers. This rhetoric legitimized budget cuts and increased policing as solutions to the city’s problems, while also construing the very populations in need of help as lacking agency and autonomy. Mutual aid organizations countered these strategies by supporting the autonomous political organizing of those most affected by the mayor’s agenda. They also acted prefiguratively, directly providing aid that they called on the city to provide. My analysis draws on my dual role as both an organizer of various mutual aid groups and an ethnographer completing my dissertation research on the same topic. I turn now to the so-called “migrant crisis.”

Starting in June 2022, Texas Governor Greg Abbot began bussing asylum-seeking migrants from Texas border towns to so-called “sanctuary cities,” cities that ostensibly made a promise not to cooperate with federal attempts to deport migrants. Many of the migrants who found themselves on these buses claimed that they were misinformed about the destination and the resources that would be available there. At the time of writing, more than 51,000 asylum seekers have arrived in New York City, with at least 31,000 in the city’s care.

As Janet Roitman writes, “crisis is an observation that produces meaning. […] When crisis is posited as the very condition of contemporary situations, certain questions become possible while others are foreclosed” (2013, 41). The Adams administration framed the influx of migrants as a “crisis,” using it as a discursive shock, laying out the necessity for austerity before implementing it. During a press conference in February 2023, for instance, a reporter asked if there would be enough money in the city’s budget to expand curbside compost pickup from a pilot program to a city-wide initiative. The mayor immediately reminded the press-corps that “we are in a migrant crisis:”

When it comes down to budget, I can’t promise anything. The asylum seekers this year, $1.4 billion. Next fiscal year, $2.8 billion. I cannot promise anything. I don’t know what’s going to happen at the border. I said it before and I’m going to continue to say it, and I’m hoping — I’m happy to see a lot of my colleagues are now joining me. We need the federal government to get involved. This is going to impact every service New Yorkers receive. Every service. My goal is not to hurt those services that we could use to benefit our city, but everything we must look at. I have to continue to manage this real budget crisis we are having and it’s being aggravated by the asylum crisis. (Adams 2/1/2023)

For Adams, the arrival of asylum-seeking migrants provided a justification for drastic budget cuts. His administration had already unilaterally slashed the budget mid-fiscal year a month prior, putting some of the largest cuts on educational services such as schools, colleges and libraries. There was one exemption for uniformed positions like police officers, citing a crime surge: “one thing we cannot ever compromise on and that’s safety.” Despite the calls for belt tightening in other agencies, on April 6th, 2023, the administration settled a contract awarding police officers from the Patrolmen Benevolent Association a base salary of $130,000, not including overtime – a pay bump of about 50%. Nor were policemen pensions discussed as a future burden.

I am focusing on Adams, but this is nothing new. Ruth Wilson Gilmore (2022) has coined the term “organized abandonment” to explain how local and state governments have supported the dismantling of welfare state capacities, decreasing social benefits while shifting the burden on households. “Crisis, then, is organized abandonment’s condition of existence and its inherent vice. To persist, systematic abandonment depends on the agile durability of organized violence” (305). In the cases herein analyzed, this police-first strategy went beyond trashing homeless and asylum seekers’ encampments. It also undermined their agency and autonomy, choosing coercion over the provision of services and allocation of resources.

A few hours after Adams gave the above quote at a press conference, the city swept a protest encampment at The Watson hotel. The Watson, like other hotels throughout the city, had been contracted out as a Humanitarian Emergency Response and Relief Center (HERRC) for newly arrived migrants. The city then planned on bussing them from this hotel on 57th St. in Manhattan to a temporary congregant HERRC at the Brooklyn Cruise Terminal in Redhook, Brooklyn. This was to be a three-month arrangement until cruise season began and migrants would need to be transferred again. The day the relocations began, migrants were told to come to the lobby of the hotel with a sheet of paper indicating the time of their eviction. The shelter staff and city agents would load about six people at a time on a city bus and send them to Redhook. The process would repeat every 45-60 minutes until the hotel was empty.

While some migrants boarded the buses to their new residency, others refused to go to Redhook, resisting the city’s decision. The refusers had seen a video of the shelter conditions circulating on Instagram and decided they would protest outside the hotel to be able to stay at the Watson. The videos showed the expanse of cots inches apart, with a sheet and pillow on top. Reports of cold temperatures in the facility were also being shared through words-of-mouth. By the evening of the first day, about fifty migrants returned from Redhook, appalled by the conditions, and initiated a protest to be able to remain at the shelter.

On the first day of the protest, migrants set up a protest encampment in front of the hotel. At first, only a few reporters, some hotel staff, and functionaries of the public agencies and non-profits providing services to the migrants were on the scene. By that night, however, the protestors had been joined by activists and various mutual aid groups that had formed during the COVID-19 pandemic. New York City had experienced what had been a mild winter; however, that week, the temperatures had quickly dropped to below freezing. Despite the cold, the migrants were willing to protest with donated blankets, tents, jackets, and hand warmers, sometimes warming up in vehicles owned by a mutual aid organizer arriving with supplies.

At the start of the pandemic, mutual aid groups had focused on addressing local concerns and needs within their neighborhoods. This event and the one at the Tompkins Square Park the Spring prior were different. Throughout the protest at the Watson or the homeless outreach at Tompkins Square Park, mutual aid groups pooled their local resources towards city-wide issues, linking up as affinity groups to support migrant political organizing. For example, a month prior to the Watson protest, there had been a speak-out by migrant residents from two HERRCs with complaints about treatment by staff and poor-quality food. This speak-out had been supported by two mutual aid groups in the Bronx, La Morada and South Bronx Mutual Aid, which had delivered meals and helped organize the press conference (IBID). These two groups, joined by others from Queens and Manhattan, showed up again to aid the Watson protest. They brought supplies requested by the migrant-activists and relayed information shared by migrants on social media. Thus they supported the goals of the protest, without leading it. Only by acknowledging the nature of this solidarity can we examine the way the city attempted to win the media war by denying the migrants agency.

City agencies tried to convince migrants to agree to sheltering at Redhook. During this standoff, the mayor’s office accused mutual aid groups of lying to the migrant protesters and preventing them from taking shelter, a media spin strongly refuted by dissenting migrants. Thus, the city only acknowledged the activists’ agency, rather than the migrants’, as instrumental in organizing the sit-in. Despite this erasure of agency, the migrants were very clear that they were organizing with intention. During a press conference held by the protesters at the Watson on January 31, Ivan, an asylum-seeker from Venezuela, said, “We are all very conscious of what we’re doing. We just want a dignified place to sleep” (qt in. Ludovici and Gurgurian 2023).

Finally, the night of February 1st, the police moved in. Hours after Adams’s speech around the budget for curbside composting quoted above, NYPD’s Strategic Response Group, the city’s riot police, dismantled the encampment. Migrants and supporters grabbed whatever supplies they could and left the scene. Some migrants went to the Redhook shelter, others stayed with organizers, while others left NYC altogether, hoping for better conditions in Canada or other US cities like Chicago.

The vignettes in this piece highlight a contrast between mutual aid politics of abundance and state politics of austerity. While the Adams administration used the “migrant crisis” to slash budgets out of a pretext of care, the mutual aid groups approached the situation at the HERRCs and homeless encampments not by making demands, but by supporting migrants’ own demands to the city through distribution efforts. This prefigurative politics of abundance pushed against a neoliberal logic of scarcity by refusing to “police need” when doing distributive labor, a practice for which formal charities are often criticized.

The main objective of mutual aid is to give material support to those who need it. In the cases analyzed above, this form of distribution politics prefigured an alternative to austerity, while also aiding protestors and making a political statement against failing policies. In fact, the very act of providing blankets and tents during the protest while eschewing the patronizing logics of state- and city-led humanitarian interventions was in itself political, as shown by the city’s framing of mutual aid activists as agitators.

Thus, we see how solidarity was a key aspect of mutual aid groups that formed in NYC during the pandemic. These groups started by focusing on neighborhood concerns. Yet, events like the ones at the Watson Hotel and Tompkins Square Park demonstrated how these groups could operate on a larger scale, through resource sharing and following the lead of others in making political demands. Refusing to lead protests, mutual aid activists amplify the voices of those with whom they are cooperating. Through this prefiguration, mutual aid invites us to imagine a world of abundant resources, cooperation, and freedom as opposed to carcerality, cops, and control.

Works Cited

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson (2022) “Beyond Bratton” in Abolition Geography: Essays Towards Liberation. Edited by Brenna Bhandar and Alberto Toscano. New York: Verso

Roitman, Janet L. (2013). Anti-Crisis. Durham: Duke University Press

Spade, Dean (2020) Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During this Crisis (And the Next). New York: Verso

You may republish this article, either online and/or in print, under the Creative Commons CC BY-ND 4.0 license. We ask that you follow these simple guidelines to comply with the requirements of the license.

In short, you may not make edits beyond minor stylistic changes, and you must credit the author and note that the article was originally published on Home/Field.