In her book, The Sustainability Myth: Environmental Gentrification and the Politics of Justice (2020, NYU Press), Melissa Checker explores the drivers and consequences of environmental gentrification in New York City. Based on ethnographic work with community activists in and beyond Staten Island, Checker traces the process through which sustainability programs and policies lead to “greening” in some (privileged, wealthy) communities and “browning” in others. In the conversation below, Brie Berry and Melissa Checker discuss the often unspoken consequences of urban sustainability, the burdens of “participatory” decision-making processes, and the challenges of doing anthropological research.

Brie Berry:

Melissa, thanks so much for this conversation, and for your wonderful book – The Sustainability Myth. I wanted to begin our conversation today with a term you describe early in the book: “sustainaphrenia,” or the frenzy of attention to climate change that results in solutions that don’t really address the primary drivers of climate change and other sustainability issues, and often make them worse. Can you talk a little bit about how you came to that term over the course of your research?

Melissa Checker:

Yeah – so I wasn’t the one who coined it. My friend and former colleague Stephen Steinberg came up with the term. We were talking about the ways in which New York City was being promoted as doing all these green things. All of this greening was happening at the same time that the people that I was working with on Staten Island were fighting off all of these facilities coming in, and they were fighting to retain their wetlands, which were being encroached on. So he coined the term and the more I had it in my head and thought about it, it really resonated with Deleuze and Guattari’s idea of capitalism and schizophrenia, and how the reality that capital is creating for us is so rife with contradictions. It really seemed to apply to what was happening in sustainability, especially with the activists I was working with, who were hearing all of the promotional discourses on one hand and then their reality really didn’t map onto them on the other. So greening and sustainability seemed to be all about abstraction. We’re told that waterfront development is somehow going to be good for flood protection. Or that getting to carbon zero through carbon trading is a great idea and we should all be pushing for it when, if you scratch the surface and look into it, you realize that it couldn’t possibly work.

So I thought it applied to this general condition we live in where we have all these contradictions and we’re being told that more development will somehow bring us away from the effects of climate change. But then the activists I was working with also kept saying to me over and over again, “the system is crazy-making” you know? And please realize that I’m talking about this kind of sociological construct of schizophrenia, not the actual mental illness. But I did see how the activists kept trying to go through the motions and do what they were told in terms of attending public meetings and going to public hearings and testifying and being these dutiful citizens and community activists and it wasn’t getting them anywhere. And in the meantime, they were just seeing things get worse and worse and spending all of their time at meetings and serving on boards, and it wasn’t having any effect. So they just started flat-out refusing.

BB:

And you describe this idea of activist overload in your book. The exhaustion and frustration of the activists you worked with was so palpable, as they struggled to make change in their communities and engage in all of the “participatory” and “democratic” processes set up by sustainability planners. You describe the use of civic engagement almost as a tool of dominance – as a way of making green development seem like some kind of a consensus when the choices were quite limited, if there were any choices at all.

MC:

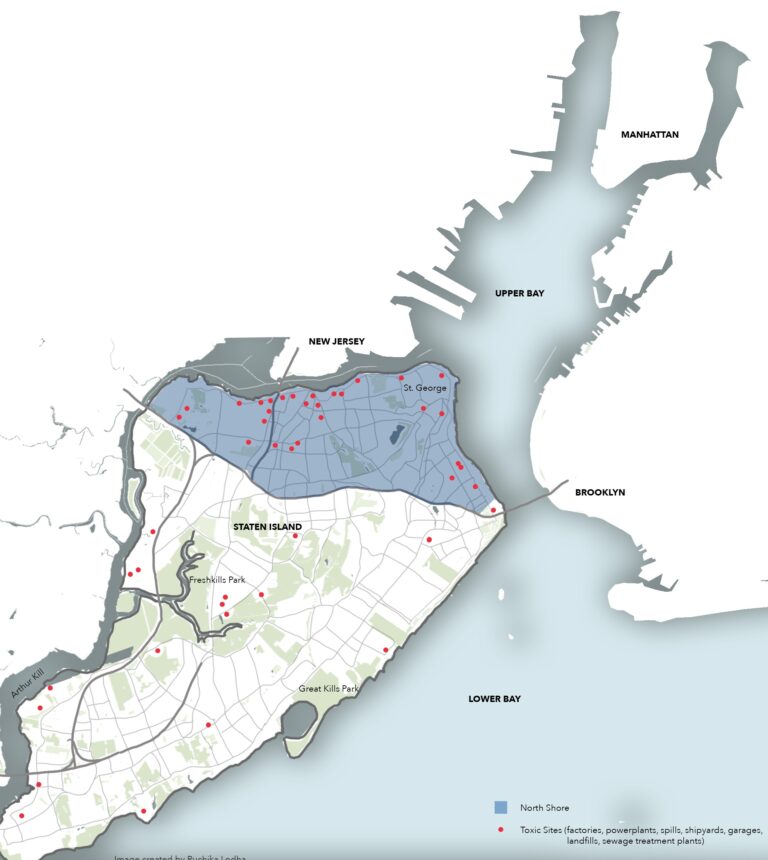

I did this field research for a long time – about 10 years or so – and I just couldn’t believe all of the multiple levels in which this “civic engagement” was screwing people over. Every week there were multiple meetings and testimonies and hearings to contribute to and things to read and weigh in on and steering committees and boards, or committees to serve on. There were also other “opportunities.” I write in the book about how the EPA had designated the North Shore of Staten Island as an environmental justice showcase community and it came with some funding, so it seemed like this great opportunity. But there were so many strings attached to it and such a narrow opening for what people could actually do with that money. That grant also required them to form a separate organization. Everybody was already very active in the community doing other things, and here they had to form this whole other organization and do all of this work that wasn’t really what they wanted to use the money for anyway…and it just was really this huge pressure on their time. It was just the epitome to me of the ways that in the name of civic engagement community members are just being sort of deputized or really burdened with extra work. And they’re supposed to be grateful to have that opportunity.

BB:

Yes! What seemed like a good opportunity to improve the community kept deviating from the path that they wanted to be on. In the end, what came out of it was not at all what they had hoped for. It just seems so deeply frustrating and flawed. I have to admit that your book really challenged me in a in a lot of ways. I just got my PhD over the summer and I was trained as a community-engaged researcher. You write about the burdens that community-engaged research can place on research participants in the name of doing good anthropology. What do you think good, community-engaged anthropology should look like?

MC:

I know – my book is such a downer! I think there are definitely things you can do, though. I think there are small, subtle ways to make a difference. For example, I would find small ways to help the community groups I was working with. I think about it in terms of reciprocity. How can I repay them – either in cash, which is preferable – find some way to funnel some cash like by hiring the group or individuals as community consultants. It’s hard to write that into grants, but sometimes you can do it. Or I offered to do something in return, like write a grant proposal. It’s not fun, and it takes a lot of time, but it definitely made me feel a lot better, and I felt more intimately involved, so it was a real payoff for me as well. But I still catch myself all the time…I was just talking to somebody who’s organizing a symposium and wanted to have some community people on it. He asked if I could help connect him, and I was like “yeah, great” and then, “they’re going to need their time compensated.” You just have to demand it. It really rankles me when people assume that speaking to a class, or to a small group of academics benefits a grassroots organization in itself. In fact, the people I worked with might do it as a favor, but they often resented not being offered some kind of reimbursement or compensation for their time. Unless they were a professional organization and already being paid for their time, “getting their message out” to a handful of people was not necessarily part of their mission.

BB:

There does seem to be this credibility game in academia, like when you talk about your research participants as friends. We are supposed to get to know people. We’re supposed to be close. And friends don’t pay friends to speak or participate. We’re supposed to have these personal relationships that cross lines between academy and community, and we often erase power when we write about them.

MC:

And people don’t talk about that very much.

BB:

It feels funny sometimes, especially when the research is close to home. I did research in my own community and it makes messy relationships.

MC:

Yeah, it does. I have also made some genuine friends in the field. But it does sound self-congratulatory to say it.

BB:

So switching gears a little – your book is all about gentrification, but also about the potential to form new political solidarities in the face of these pressures.

MC:

New York is a really good place to study that because we have several really active environmental justice organizations that have been active for a long time in different boroughs. And they’ve been dealing with this issue for a while, because they’re all in similar types of communities. So if one of them blocks a waste incinerator or something then it’s very likely – and this has happened – that it gets sited in another one of these communities. So if there is one neighborhood within this network of environmental justice groups then they try to be really aware that blocking something from one place means that they block it from every place. But also, you need city-wide policies. If there’s a big picture city-wide policy where you’re looking at the burdens of each neighborhood and then making sure that every neighborhood gets its fair share, then you won’t just be kind of moving things from one over-saturated neighborhood to another.

BB:

Speaking of policy – one of the key arguments in your book is that there’s this tradeoff that folks are being forced to make between community improvements and gentrification. One example you give is a market-based brownfield remediation program for contaminated sites. The way this program is structured means that communities with contaminated sites are only able to address contamination if they accept subsequent redevelopment and gentrification. If communities aren’t willing to make those tradeoffs, or aren’t seen as lucrative investments for developers, they’re left with continued contamination because the only option for site remediation is one that relies on markets. It just seems like people are stuck when the policies are designed in this way. Do you see any way out of this?

MC:

Yeah, it’s a good question. I think if you’re remediating a whole bunch of brownfields in a lucrative community like Williamsburg or Greenpoint for redevelopment, there could be some way to redistribute some of those resources to the outer boroughs that aren’t getting that private money for investment. In terms of not displacing people…this is a very controversial thing to say, but I think the main problem with gentrification is displacement. If there could just be neighborhood improvements without neighborhood displacement that would put a whole different spin on things and would make it more like revitalization. That would require more affordable housing policies. Maybe expanding the number of rent-controlled apartments in New York City instead of continuing to shrink them. Expanding things like Section 8. We have such a rich history of affordable housing programs in New York that were for everyone – middle class families, working class families, and we’ve just been chipping away at them. Maybe it’s time to build them back up.

BB:

I can’t think of a better way to end this piece than with that hopeful policy recommendation. Melissa, thanks for such a wonderful conversation, and an excellent book. It’s been such a pleasure to talk with you and learn from you. Thanks, also, to Home/Field for giving us the space to share our conversation with others.

You may republish this article, either online and/or in print, under the Creative Commons CC BY-ND 4.0 license. We ask that you follow these simple guidelines to comply with the requirements of the license.

In short, you may not make edits beyond minor stylistic changes, and you must credit the author and note that the article was originally published on Home/Field.